“No I know you, I can feel you, you’re a good girl.”

In most cases, you smile when being told that you’re a good person. Maybe because you’re kind and you radiate positive energy. This definition implies that anyone can be good. However in my world, good carries a different meaning. It comes with a suggested lifestyle. It’s not an adjective, it’s a label.

In most cases, you smile when being told that you’re a good person. Maybe because you’re kind and you radiate positive energy. This definition implies that anyone can be good. However in my world, good carries a different meaning. It comes with a suggested lifestyle. It’s not an adjective, it’s a label.

I’m a London born girl in my mid-twenties with Pakistani roots. As commonly heard from most children of diasporic South Asian parents, my identity is a merge of the East and West. During childhood I was taught Islamic fundamentals, whilst being raised in a house of South Asian culture and language.

As a young girl, I was told that my body is a jewel which must be protected. Once, my aunt explained how girls have a radar around them. She used her arm length to demonstrate a circumference around her body and called it “your personal zone.” Males, who were always described as the feared Other, should never enter this zone before marriage. My mother drilled into my head that a girl must uphold her honour and refrain from following the ideals of the West. As I grew into my teens, unlike the society around me, saving myself for my ideal husband was my glory and I knew that straying will lead to shame for my family and dishonour for me. I was glad that I was a good girl.  I don’t shame those who enjoy “the Way of the West”, and neither parents like mine who try to teach their kids values they think will benefit them. However I object to the lack of middle ground found between both cultures. Talking to my dad about anything other than my education was unheard of. My mother, God bless her, who had all the burden of raising obedient children, only focused on maintaining good values. When I became a young adult, I felt stuck between the curfew hours and my desire to start seeing the world with my own eyes.

I don’t shame those who enjoy “the Way of the West”, and neither parents like mine who try to teach their kids values they think will benefit them. However I object to the lack of middle ground found between both cultures. Talking to my dad about anything other than my education was unheard of. My mother, God bless her, who had all the burden of raising obedient children, only focused on maintaining good values. When I became a young adult, I felt stuck between the curfew hours and my desire to start seeing the world with my own eyes.

I wasn’t after the drugs, sex and alcohol life. Still, I was made to feel like a disreputable girl if I stayed out late, dressed up or slept over at friends. I already stood out in society for not having relationships, going clubbing or wearing revealing clothes – and these rules I accepted. But I struggled to understand why my social life was restricted to the time of day and the gender of my peers. When questioned, it was always “good girls are not seen on the streets after dark… it’s dangerous. What will people say if they see you coming home late?” As I aged, harmless things that I wanted to enjoy became added to the list of “what doesn’t make me a good girl.”

Life soon taught me that my culture’s upbringing wasn’t fool proof. In my early twenties, I still had hopes of remaining a “Good Girl” who innocently befriends “The One”, which leads to a pious respectful happy-ever-after. Instead, I trusted the wrong guy just like every other girl I tried so hard not to be like. On top of that, the traditionalism my parents absorbed themselves into, solidified the barrier between us. Unable to express my feelings, I felt ashamed for breaking their trust.  I loved this man and entrusted my soul into his hands. We shared every detail of our lives, and his love overpowered all the words of wisdom I had been taught. I became an extension of his identity. I felt relieved that obeying my parents with having the intentions of only marriage, had paid off. When he broke my heart and left, my dream vanished. “Oh no … now I have an ex”, I thought. “How will I be a good girl now?” You see, to most people heartbreak is normal, but in my world this was EXACTLY what I had been brought up to avoid. All those embedded values were at stake and drifting from them felt like I had ruined it for myself. I had let my mother, my aunt and myself down. Gradually, this made me lose respect for myself.

I loved this man and entrusted my soul into his hands. We shared every detail of our lives, and his love overpowered all the words of wisdom I had been taught. I became an extension of his identity. I felt relieved that obeying my parents with having the intentions of only marriage, had paid off. When he broke my heart and left, my dream vanished. “Oh no … now I have an ex”, I thought. “How will I be a good girl now?” You see, to most people heartbreak is normal, but in my world this was EXACTLY what I had been brought up to avoid. All those embedded values were at stake and drifting from them felt like I had ruined it for myself. I had let my mother, my aunt and myself down. Gradually, this made me lose respect for myself.

I began to touch into the life I once forbade. Viewing life through the smoke I exhaled, I dived into a typical rebound with someone who called himself a liberal. Being as western as I could to enjoy the freedom I craved, I still experienced no sign of contentment. He wasn’t religious or traditional and yet his insecurities caused a jealousy I found suffocating. “Too much makeup, your chest is too on show, why are you laughing at his jokes, you look too pretty, you can’t go partying, you can’t sit in his car late…” I was confused. Is there a good and bad girl even in the “bad life”? I felt like I was living under my parents’ pressure again.

So I spoke up – wrong was wrong and I wanted to object to it. Speaking against the acts of a man turned me into a bad girl again! Just by fighting for what I had come to believe in, I was called “unwomanly”, because I didn’t gently accept whatever he threw at me. Any form of opposition deflated his ego, so calling him out made me a disrespectful girl who didn’t deserve to be loved, nor respected. He told me I was nothing and God knows I really felt it. After months of tug of war, I broke free from the ropes and gave myself time to heal alone. Emotional infidelity and psychological abuse affect a person’s mind in ways that can cause clinical illnesses.

So I spoke up – wrong was wrong and I wanted to object to it. Speaking against the acts of a man turned me into a bad girl again! Just by fighting for what I had come to believe in, I was called “unwomanly”, because I didn’t gently accept whatever he threw at me. Any form of opposition deflated his ego, so calling him out made me a disrespectful girl who didn’t deserve to be loved, nor respected. He told me I was nothing and God knows I really felt it. After months of tug of war, I broke free from the ropes and gave myself time to heal alone. Emotional infidelity and psychological abuse affect a person’s mind in ways that can cause clinical illnesses.

I share my story to raise the following questions to the parents of my community:

Why don’t we have open conversations at home? There’s no space for honesty but only fear of consequence.

Why impose your ideal norms upon your children without recognising that they bear the brunt of cultural clashes?

My beloved parents, do you really trust me if you can’t give me freedom? Your intentions may be right but the pressure you execute is wrong. You call yourself Muslim but who do you really fear God, or the people who talk? I also want to question myself and all the other fallen Asian girls.

I also want to question myself and all the other fallen Asian girls.

Why don’t we hear our own voices and instead stick to these flawed labels? The other day a man, unaware of my past, told me: “No I know you, I can feel you, you’re a good girl.” I wanted to scream! I now refute this term.

What is a good girl? Is she someone who always listened but for once wanted to be heard? Can she be a girl who meant well but failed?

I have always been a person who wants to stand correct in all aspects of my life. I am still learning to have faith in who I am and to view my experiences as a means of empowerment rather than tales of my defeats. The truth is that this notion of a perfect girl is just a man-made construct improvised from fragments of misinterpreted customs and traditions. It serves as a template to demean females into a standardised way of living. The flaws of this system stem from the awful effects of patriarchy and its urge to control women. Until we don’t come together as women to defy all that leads us to believe that we’re anything other than a decent human being, these outdated cultures will continue to birth fathers and husbands who understand us in no other terms than good and bad.

Words by an anonymous friend

Artwork by Sreyashi Tinni Bhattacharyya:

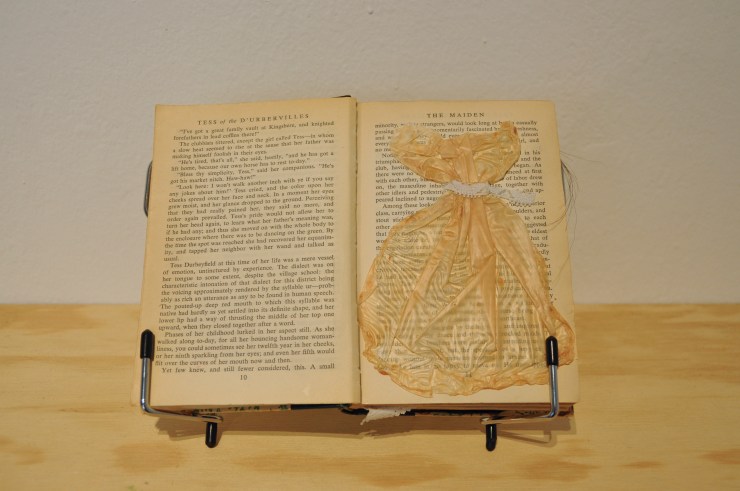

didar, mammar, amar (grandaunt’s, mom’s, mine) (2016)

From return to the bari / body

Cotton, wood, cotton thread, beads, rice, and nails

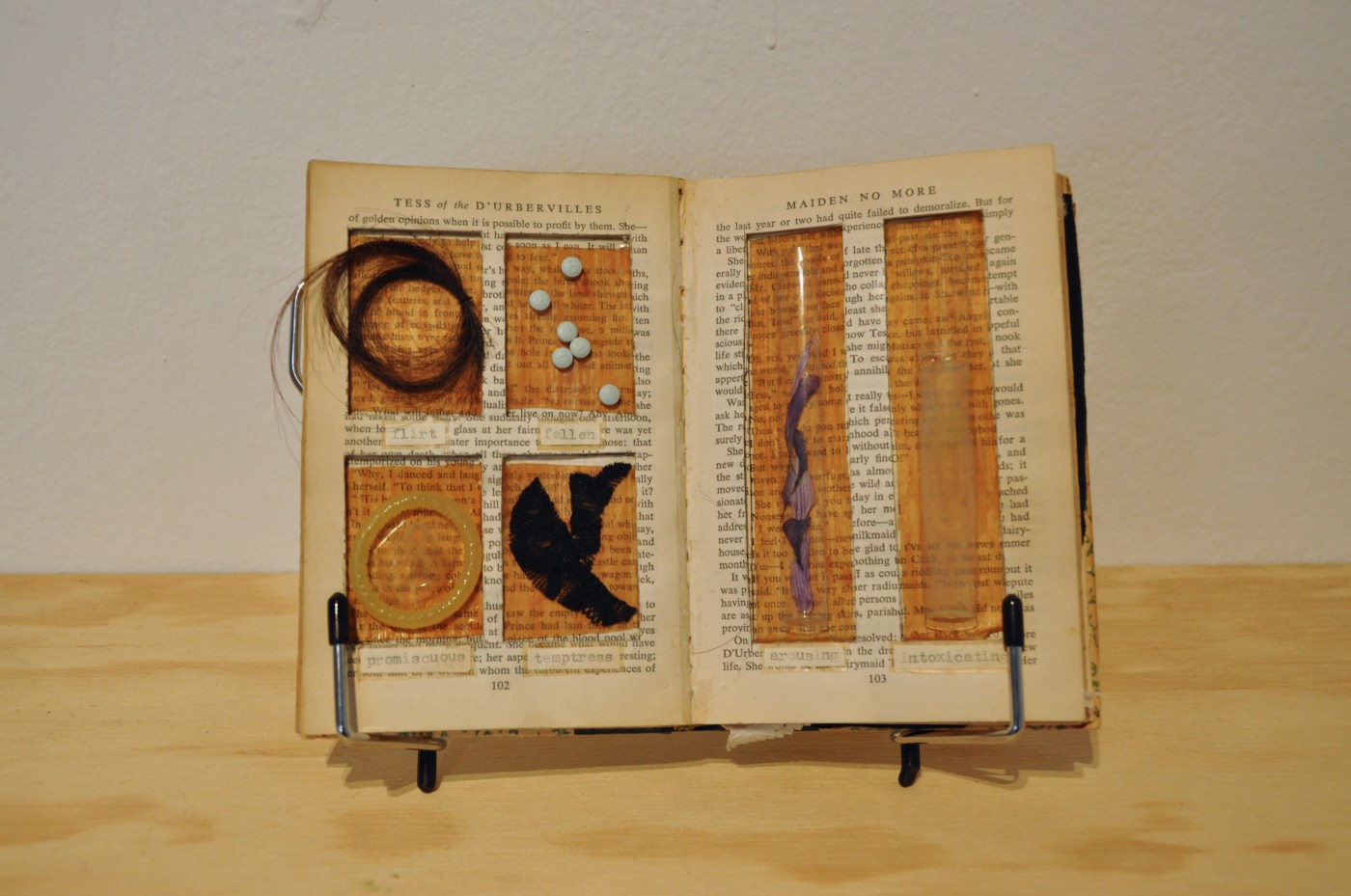

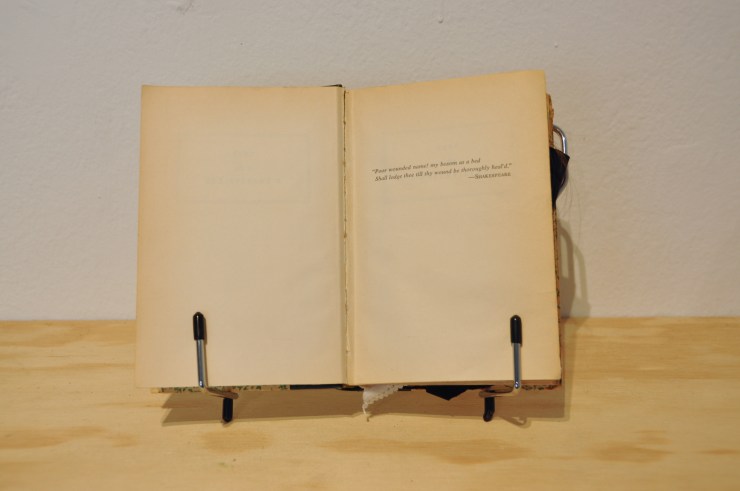

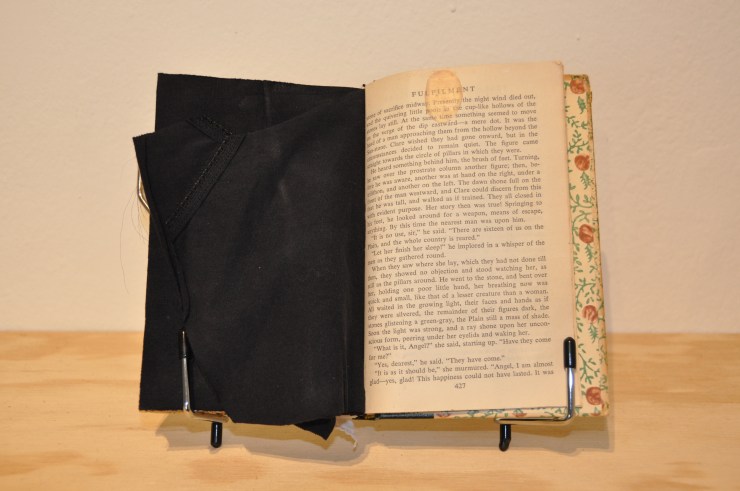

TESS of the D’URBERVILLES (2013)

Found book, latex, lace, condom, triprevifem, flowers, underwear

Sreyashi (Yashi or Tinni, preferred) is a young Bengali artist, researcher, and curator who is currently working and studying in London, UK. Born in New Delhi, Yashi grew up moving every three (sometimes two) years to a new country and a new home. This experience has shaped a lot of her work, as she enjoys exploring the processes behind the development of ones’ identity and the conceptualization of varying perspectives and histories. Her studio practice lies at the intersection of her art historical, scientific, and political research as she addresses themes of womanhood, heritage, labor, power, and control.